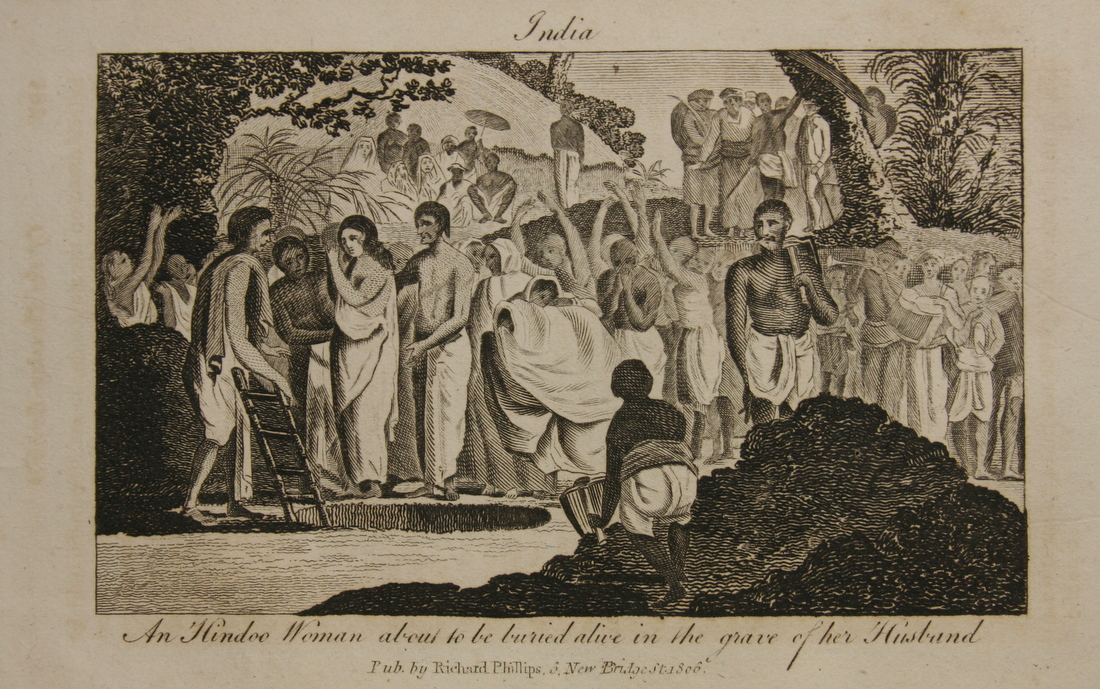

A widow about to be buried alive in her husband's grave (Wikimedia Commons). Do we all share the same sense of right and wrong?

What, ultimately, is the basis for morality? In a comment on a previous post, fellow columnist Fred Reed argued that some things are self-evidently wrong, like torture and murder. No need to invoke the Ten Commandments or any religious tradition. Some things are just wrong. Period. This is a respectable idea with a long lineage. It's the argument of Natural Law. All people are born with a natural sense of right and wrong, and it is only later, through vice or degeneration, that some can no longer correctly tell the two apart.

The idea began with the Stoics of Ancient Greece. They believed that the universe is governed by laws and that everyone naturally wishes to live in harmony with them, thanks to the divine spark that exists in all of us. In reply, the Epicureans argued that the laws of the universe are indifferent to humans and their problems. We alone define right and wrong.

The Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) worked out a compromise that divided Natural Law into general precepts and secondary precepts. The former are known to all men but can be hindered "on account of concupiscence or some other passion." The latter "can be blotted out from the human heart, either by evil persuasions [..] or by vicious customs and corrupt habits, as among some men, theft, and even unnatural vices, as the Apostle states (Rom. i), were not esteemed sinful" (Aquinas, Summa Theologica I-II, Q. 94, Art. 6). Aquinas lived at a time when Christian morality had already penetrated deeply into the hearts and minds of Europeans. It was continually being violated, of course, but violators typically knew they had done wrong and they typically tried to justify their wrongdoings on Christian grounds, or seek absolution. Aquinian Natural Law thus closely approximated moral reality, much as Newtonian physics would long remain a good approximation of physical reality.

Things changed from the 16th century on, as Christian Europe spread outward into Africa, Asia, and the Americas. It became evident that notions of right and wrong were not everywhere the same, or even similar. One example was sati, the Indian custom of burning a widow alive on her husband's funeral pyre. Though supposedly voluntary, it usually involved the tying of her feet or legs to prevent escape. She could also be buried alive, as a 17th century traveler noted:

In most places upon the Coast of Coromandel, the Women are not burnt with their deceas'd Husbands, but they are buried alive with them in holes which the Bramins make a foot deeper than the tallness of the man and woman. Usually they chuse a Sandy place; so that when the man and woman both let down together, all the Company with Baskets of Sand fill up the hole about half a foot higher than the surface of the ground, after which they jump and dance upon it, till they believe the woman to be stiff'd. (Tavernier, 1678, p. 171; see also Sati, 2014) When the British sought to ban the practice, they appealed to notions of right and wrong, but to no avail. Defenders of saticonsidered it right and even honorable. The debate was finally resolved by the logic of force, as set forth by the British commander-in-chief:

This burning of widows is your custom; prepare the funeral pile. But my nation has also a custom. When men burn women alive we hang them, and confiscate all their property. My carpenters shall therefore erect gibbets on which to hang all concerned when the widow is consumed. Let us all act according to national customs! (Napier, 1851, p. 35)

Enlightenment thinkers attributed this custom and others like it to degeneration from an original state of goodness. Thus was born the idea of the Noble Savage. Yet this idea, too, came under attack with the realization that even simple "uncorrupted" societies may have very different attitudes toward human life, as seen in the torturing of captives, the abandonment of weak or deformed children, and the killing of old men and women:

The problems posed by limited resources and old peoples' dependence are sometimes resolved in an extreme way: killing, abandoning, or exposure of the elderly—what anthropologists call gerontocide. Cross-cultural studies show that such treatment is more common than we might suppose. Maxell and Silverman found evidence of gerontocide in a little over 20% of 95 societies in a worldwide sample (Silverman, 1987). Glascock uncovered abandonment of the elderly in 9 of the 41 nonindustrial societies in his sample—and reports of killing old people in 14 of these societies. (Bengtson and Achenbaum, 1993, p. 110)

This kind of thing may seem unfortunate but justifiable among nomads. Sometimes, the elderly just have to be left behind. But we also see elder abandonment in sedentary peoples, like the Hopi of the American southwest:

As long as aged men controlled property rights, held special ceremonial offices, or were powerful medicine men, they were respected. But "the feebler and more useless they become, the more relatives grab what they have, neglect them, and sometimes harshly scold them, even permitting children to play rude jokes on them." Sons might refuse to support their fathers, telling them, "You had your day, you are going to die pretty soon." (Bengtson and Achenbaum, 1993, pp. 108-109)

Whenever such accounts come up at anthropological conferences, there is a certain malaise. Some will blame European contact for the devaluing of human life. Others, however, will present similar facts that often predate the coming of traders or missionaries. I remember one speaker who presented evidence of cannibalism at an Inuit site. This wasn't an isolated case, such as might happen in extreme circumstances of starvation. There seemed to be an accumulation of human bones, of Indian origin, with cut marks on them. The findings were later published:

The remains of at least 35 individuals (women, children, and the elderly) were recovered from the Saunaktuk site (NgTn-1) in the Eskimo Lakes region of the Northwest Territories. Recent interpretations in the Arctic have suggested a mortuary custom resulting in dismemberment, defleshing, chopping, long bone splitting, and scattering of human remains. On the evidence from the Saunaktuk site, we reject this hypothesis. The Saunaktuk remains exhibit five forms of violent trauma indicating torture, mutilation, murder, and cannibalism. Apparently these people were the victims of long-standing animosity between Inuit and Amerindian groups in the Canadian Arctic. (Melbye and Fairgrieve, 1994) When I talked with the speaker after his presentation, he seemed apprehensive. How would people react?

He needn't have worried. The noble savage is still alive and well. Strangely enough, this kind of thinking has seeped even into the missionary mindset, as I discovered during my last few years at the United Church of Canada. I was surprised to learn just how little our mission work involved teaching of Christian morality:

"Do you talk to these people about the Christian faith?"

"Not unless they specifically request it.""Do you at least have Christian literature on display?""No, we're not allowed to do that."Things aren't much better in the fundamentalist churches. I remember attending a Pentecostal presentation on "the cause of Third World Poverty." I thought the talk would focus on cultural values. Instead, we were told that the cause is ... lack of infrastructure. The Third World is poor because it doesn't have enough roads, bridges, and buildings.

The modern world has bought so much into the argument of Natural Law that the entire Christian enterprise now looks like a waste of time. There was no need for missionaries to fight barbaric customs, since there were no barbaric customs to be fought. All of that was one big misunderstanding. Christian mission work is now limited to good works, apparently in the belief that all humans share the same moral framework and that it's enough to set a good example. If you act nice, other people will get the message and likewise act nice.

A hazardous assumption

Christianity has been killed by its success. It has so thoroughly imposed its norms of behavior that we now assume them to be human nature. If some people act contrary to those norms, it's because they're "sick" or "deprived." Or perhaps something is misleading us and they're really acting just like everyone else.

For two millennia, the Christian faith has profoundly shaped the culture of European peoples, allowing very little to escape its imprint. This is especially so in attitudes toward the taking of life. Beginning in the 11th century, the Church allied itself with the State to punish murder, which previously had been a private matter to be settled through revenge or compensation. At the height of this war on murder, between 0.5 and 1.0 % of all men of each generation were sentenced to death, and a comparable proportion of offenders died at the scene of the crime or in prison while awaiting trial. Meanwhile, homicide rates plummeted from between 20 and 40 per 100,000 in the late Middle Ages to between 0.5 and 1.0 in the mid-20th century (Eisner, 2001). The pool of violent men dried up until most murders occurred under conditions of jealousy, intoxication, or extreme stress. Yes, people got the message to act nice, but the message was not delivered nicely. By pacifying social relations, Church and State also created a culture that rewarded men who got ahead through trade and hard work, rather than through force and plunder. It became easier to plan for the future and develop what came to be known as middle-class values: thrift, sobriety, and self-control. Popular tastes changed accordingly, as seen in the decline of cock fighting, bear and bull baiting, and other blood sports (Clark, 2007; Clark, 2009a; Clark, 2009b). Were these changes in behavior purely cultural? Or was there also a steady removal of violent predispositions from the gene pool? It's only now that a few scholars are beginning to ask such questions, let alone answer them.

Towards a new perspective ...

The idea of Natural Law is true up to a point. All humans have to face certain common problems that have to be solved in more or less the same way. Kinship, for instance, matters in all human societies, at least traditional ones. Marriage and family are likewise universal.

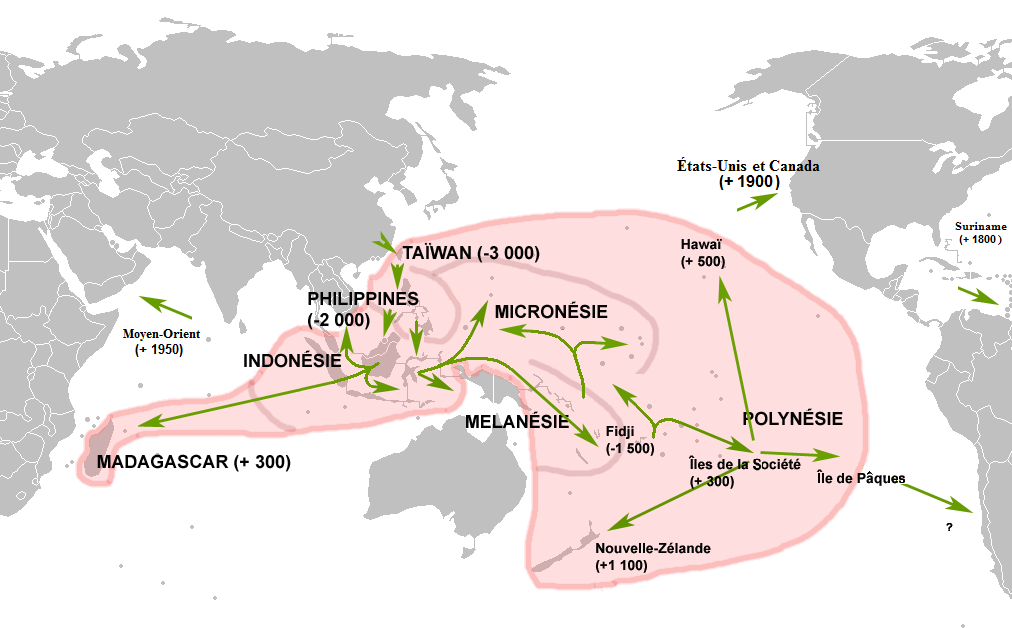

But even these "universals" vary a lot. There are many kinds of kinship systems, including some with relatively weak kinship and a correspondingly stronger sense of individualism. Mating systems likewise vary a lot. Monogamy makes sense in non-tropical societies where the mother cannot feed her children by herself, particularly in winter. It makes less sense where the mother can provide for her children with minimal assistance.

Human societies similarly differ in their treatment of murder. There is a general tendency to limit the taking of human life, but the variability is considerable. In some societies, murder is so rare that instances of it are thought to be pathological. The murderer is said to be "sick." In other societies, every adult male has the right to use violence to settle personal disputes, even to the point of killing. If he abdicates that right, he's no longer a real man.

The same "problem" will thus be solved in different ways in different places. Over time, each society will develop a "solution" that favors the survival and reproduction of certain people with a certain personality type and certain predispositions. So there is no single human nature, any more than a single Natural Law. Instead, there are many human natures with varying degrees of overlap.

... and the take-home message?

While certain notions of right and wrong can apply to all humans, much of what we call "morality" will always be population-dependent. What is moral in one population may not be in another.

Take public nudity, particularly of the female kind. This is less of a problem in places like Finland where polygyny is rare and sexual rivalry among men less intense. It's more of a problem where the polygyny rate is higher but men still have to invest a lot in their offspring. In such a setting, men will be more jealous, more fearful of cuckoldry, and more insistent on measures to ensure exclusive sexual access. Such insistence can lead to extreme practices like sati. More generally, it leads to demands for modesty in female dress.

This is not to condone the dress codes that prevail in some countries, but we should try to understand the circumstances that give rise to them. Above all, there are limits to what we can impose on other societies. While sati has no justification anywhere on this planet, there may be practices that are warranted in some societies but not in others.

References

Aquinas, T. (1265-1274). Summa Theologica, Part I-II (Pars Prima Secundae) From the Complete American Edition, Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Project Gutenberg

http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/17897/pg17897.htmlBengtson, V.L. and W.A. Achenbaum. (1993).The Changing Contract across Generations, Transaction publ.

Clark, G. (2007). A Farewell to Alms. A Brief Economic History of the World, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Clark, G. (2009a). The indicted and the wealthy: Surnames, reproductive success, genetic selection and social class in pre-industrial England.

http://www.econ.ucdavis.edu/faculty/gclark/Farewell%20to%20Alms/Clark%20-Surnames.pdf Clark, G. (2009b). The domestication of man: The social implications of Darwin. ArtefaCTos, 2, 64-80.

http://campus.usal.es/~revistas_trabajo/index.php/artefactos/article/viewFile/5427/5465 Eisner, M. (2001). Modernization, self-control and lethal violence. The long-term dynamics of European homicide rates in theoretical perspective, British Journal of Criminology, 41, 618-638.

http://bjc.oxfordjournals.org/content/41/4/618.short Melbye, J. and S.I. Fairgrieve. (1994). A massacre and possible cannibalism in the Canadian Arctic: New evidence from the Saunaktuk site (NgTn-1), Arctic Anthropology, 31, 57-77.

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/40316364?uid=3739448&uid=2&uid=3737720&uid=4&sid=21104564497747Napier, W. (1851). The History of General Sir Charles Napier's Administration of Scinde: And Campaign in the Cutchee Hills, London: Charles Westerton.

Sati (practice). (2014). Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)Tavernier, J-B. (1678).The six voyages of John Baptista Tavernier, London: R.L. and M.P.

.jpg?uselang=fr)

_-_1.jpg?uselang=en-ca)